A Brief History of Amami Oshima

The island of Amami Oshima has a complex history because of its location off the Asian mainland and between the main Japanese islands and Okinawa. Despite being bordered by powerful neighbors, the island developed a distinct culture all its own, a combination of different influences and shared similarities.

Ancient chronicles record the island presenting tribute to nearby Kyushu in the seventh and eight centuries, though this practice seems to have ceased in later years. In the fifteenth century, Amami Oshima fell under the administration of the Ryukyu Kingdom, which was centralizing its power over the area around Okinawa. Though the villages were controlled through an administrative system involving priestesses called noro, Amami Oshima was generally autonomous. Due to the Ryukyu Kingdom’s strong cultural and trade relations with the Asian mainland, Chinese influences affected Amami Oshima and the other islands that were part of the kingdom.

Invasion from the North

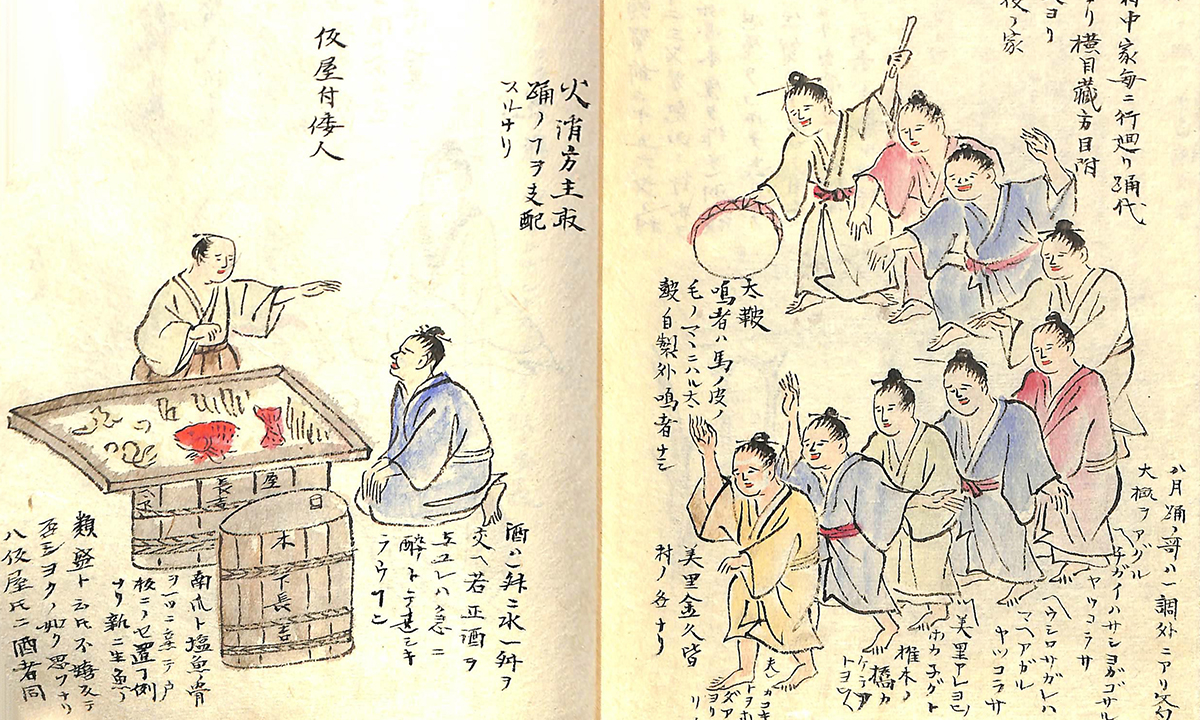

Photo provided by the Amami City Museum

Photo provided by the Amami City MuseumThe Satsuma domain, from the southern Japanese island of Kyushu, invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1609, and the Amami Islands were ceded to Satsuma. Although the pretense was that the islands were still part of the Ryukyu Kingdom, and islanders were able to maintain their traditional social structure, political and administrative authority shifted to the hands of the Satsuma domain. Economically, the island was treated as a colony, and the people were forced to give up rice cultivation and focus on sugarcane production, which was much more profitable for the Kyushu-based domain. Islanders were forced to pay taxes in sugar in return for food and other necessary supplies, and for over two centuries life was a struggle for most of the population.

Part of the Japanese Nation

Photo provided by the Wide Area Administration Association of Amami Islands

Photo provided by the Wide Area Administration Association of Amami IslandsThis colonization continued until 1879, when the Meiji government annexed the Amami Islands and they officially became part of Japan. During World War II, Amami Oshima was the target of Allied air raids, which destroyed much of Naze, the island’s largest city (present-day Amami City). After Japan’s defeat, the Allied occupation separated the Amami Islands, Okinawa, and the Nansei Islands from Japan, and placed them under direct US military rule. A concerted effort by activists on Amami Oshima led to its reversion to Japan in 1953, ending centuries of being caught in the middle of shifting geopolitical winds. Today, Amami Oshima is part of Kagoshima Prefecture, and welcomes visitors interested in its complex history, melting-pot culture, and natural attractions.

Sugarcane

It is hard to miss the sprawling fields of sugarcane (satokibi) that cover the agricultural fields of northern Amami Oshima—the jointed stalks and palmlike leaves are often seen bordering both sides of local roads. The cane grows up to 4 meters or more before being harvested in the winter months. Cultivation of satokibi on Amami Oshima is said to have started over 500 years ago, but it became the island’s main crop in the mid-eighteenth century. The Amami Islands were ideal for growing the cane, and sugar was in high demand on mainland Japan. The Satsuma domain saw sugar production as a way to bolster their finances, and ordered that harvested sugarcane be turned over by the islanders as a kind of tax. In return, the islanders received rice and other necessities. This led the islanders to give up rice cultivation and turn their fields to sugarcane. Today, Kagoshima Prefecture produces almost 40 percent of Japan’s sugarcane.

The Process

The brown sugar made from sugarcane has many nutrients, including minerals and vitamins, that are retained in the simple refining process. The first step is crushing and squeezing the stalks to get the juice, which has a sugar content of 23 percent at the peak harvesting period in February and March. This juice is filtered, then boiled for several hours until it condenses into a thick syrup, which is placed on flat surfaces to dry. The resulting blocks of brown sugar have a variety of uses. People in Amami Oshima eat small bits with tea, and use the powder in cooking. Some of the sugar is sold as a sweet souvenir of the island, while most is sent to the mainland as raw sugar for further processing. Visitors can watch brown sugar being made at a number of locations on the island. Those interested should contact the tourist center for more information.

Spiritual Life

Although Amami Oshima has been culturally connected with mainland Japan since prehistoric times, it was deeply influenced by the Ryukyuan culture, and the island’s religious beliefs and social activities still reflect those traditions.

Ryukyuan beliefs were based on ancestor veneration and had ancient animistic roots, much like Japan’s indigenous Shinto religion. The creation myth centered on the goddess Amamikiyo, which likely led to the belief in the spiritual superiority of women. Traditionally, women not only played the primary religious role in the home but also were the spiritual leaders of the local community.

Religion and History

During the heyday of the Ryukyu Kingdom, especially the reign of King Sho Shin (1477–1526), administrative officials governed through noro, priestesses who performed the religious rituals of each community. Although the Satsuma domain introduced Zen Buddhism after effectively taking control of Amami Oshima in 1609, Buddhism remained largely the realm of Satsuma officials. It made little headway into the lives of the islanders, and no Buddhist temples from this period remain. The government promotion of Shinto during the Meiji era (1868–1912) was matched by a renewed push from both the Jodo Buddhist sect and Catholic missionaries. Although these more recent religious arrivals have gained ground, there is still a deep respect for Ryukyuan religious culture. There are no longer any noro priestesses on the island, but many ancient rituals have survived as part of festivals and other events, and spiritual sites are still treated with great reverence.

Noro Priestesses

After Amami Oshima became part of the Ryukyu Kingdom in the latter part of the fifteenth century, the spiritual lives of the island’s communities came to be led by noro, village priestesses who were appointed by the royal government. They acted as religious administrators, responsible for praying to the gods for the community’s prosperity. A museum in the town of Uken displays a certificate from a Ryukyu king appointing a noro to her post in 1594. There are a number of other noro-related items on display, including the white robes worn at ceremonies, cabinets in which religious articles were stored, and colorful fans. The noro used these fans to call and welcome deities, and their illustrations of the mythical fenghuang bird, known in Japanese as ho-o, show how deeply Ryukyuan culture was influenced by China.

Talking to the Gods

Noro held a prestigious position, although their lives and living conditions were no different from those of other villagers. They could even marry and have children. On ceremonial days, the noro would put on their white robes and communicate with the gods on behalf of their village, aided by their mostly female assistants. The Satsuma domain of southern Kyushu took over the appointment of noro after Amami Oshima and other islands came under its control, but the formal system ceased when the kingdom was abolished in 1879. The noro were so central to village life that their influence continues to be felt at many of the island’s festivals. Older islanders share tales that have been passed down for generations about the awe-inspiring powers of some legendary noro.

The Shaman Tradition

Yuta, female spirit mediums or shamans, are often confused with noro. Yuta were not part of the governing administration, but rather independent agents. Unlike the noro, whose prayers were focused on the security and prosperity of their community, the yuta acted as psychic mediums by conveying the will of the gods to individuals—a role similar to a spiritual counselor. They would become possessed, and often wore masks that represented their transformation into a channel for the voice of the spirits. There are still some reminders of this tradition on the island in the form of fortune-tellers, who usually operate out of their homes.

Kamimichi

One of the village noro’s greatest responsibilities was to facilitate the annual visit of the deities (kami) and ensure their enjoyment while prayers were made for a good harvest. Most of Amami Oshima’s villages face the sea, their backs to the mountains. The deities protecting the village are said to reside in the heavens over the nearby kamiyama, or “god mountain,” while the gods of fertility live in the land of Neriya Kanaya, far across the sea. Many villages have a tachigami, a nearby rock or small island that the kami can use as a signpost to find their way to the community. Another feature found throughout the island is the kamimichi, or “path of the gods,” a route through each village that the gods use on their visits. The route meanders along small roads and narrow alleys to the myaa, a village square. No matter how narrow the path may be—sometimes barely more than shoulder-width—the route is kept scrupulously clean and free of obstructions all year round.

Visits from the Gods

On festival days, the deities come to the village from the sea and mountain via the kamimichi, and are welcomed and entertained. This was traditionally the task of the noro, and prominent local women still play the main role, with support from villagers. The myaa is an important site for many rituals, including a respectful visit from a parade of men, both young and old. Later, they will participate in the highly anticipated sumo matches held at the local dohyo, the earthen-floored ring that is every community’s pride. At the end of the day, the villagers bid farewell to the deities, who return to their homes, hopefully entertained and pleased with their visit.

Yokai and Talismans

Amami Oshima is home to a yokai, one of the mythical creatures that have appeared throughout centuries of Japanese folk tales and folk art, so visitors might want to keep their eyes peeled.

The kenmun is about the height of a child, with red eyes and elongated legs and arms. It shares many similarities with the kappa water sprite, one of the most famous Japanese yokai, and the kijimuna, its Okinawan tree-spirit equivalent. It is covered in reddish fur and is said to smell like a yam, though it can apparently change its appearance, disguise itself as a plant, or disappear. Like the kappa, the kenmun has a depression on its head that holds a liquid that gives it power. It also is said to love sumo, and tends to challenge people it encounters to a wrestling match.

How to Respond to a Sighting

The kenmun’s spirit resides in large banyan trees or sea fig trees, and some believe cutting the tree will call down a curse. It goes to the beach at night to feed on fish and shellfish, and is usually not dangerous to humans; in fact, there are stories of kenmun helping people carry firewood from the forest. It can, however, be a prankster and cause mischief, stealing food or posing as a human and giving wrong directions to people who are lost. Sightings of this yokai have decreased over time, most likely because there are few banyan and sea fig trees still standing. Perhaps the best thing to do if you see one is just walk away—better to play it safe than have to wrestle the legendary creature.

Spider Conch Talismans

Ancient beliefs run deep on Amami Oshima. Visitors to the island villages may notice spider conch (Lambis chiragra) shells placed at the gate, on the corners of walls, or at the entrance of houses. The shells of this large sea snail are about 20 centimeters long, and are called suijigai (water character shells) in Japanese because their shape resembles the kanji character for water. They are traditionally believed to ward off evil spirits and protect dwellings from fire.

Island Culture

Sumo and Dohyo

Amami Oshima probably has more dohyo (earthen-floored sumo wrestling rings) per capita than any other part of Japan. There are over 140 of these rings in villages all over the island. Some are more elaborate than others, but most are in excellent condition with a well-made roof overhead, a mark of how popular and deeply entrenched the sport is in the island’s culture.

The Traditional Style

Sumo on Amami Oshima once resembled the Okinawan style of wrestling. Much like wrestling traditions from Korea and Mongolia to Turkey, grappling was key, and matches would start with each wrestler gripping his opponent. These days, however, it follows the Japanese tachiai style, in which wrestlers burst out of a crouch and try to push their opponent out of the ring or throw them to the ground.

All Contenders Welcome

The island has produced a number of champions, both professional and amateur. The best wrestlers tend to train at one of the local clubs around the island with dedicated coaches. In these clubs, wrestlers as young as five or six years old begin a hard training regimen. But that doesn’t stop anyone from trying out their skills in the ring. Sumo matches are an integral part of local festivals, and are open to all—that is, anyone willing to step into the ring and dedicate themselves to the gods. These occasions are especially important to smaller villages as a way of expressing community pride.

Reef Fishing

The coral reef surrounding Amami Oshima is teeming with sea life, and has been a source of sustenance for the islanders for centuries. The shallow sea from the coast to the edge of the reef is called ino, and at low tide men and women flock there to collect many kinds of seafood. Local residents know that izari, (night harvesting) brings the best results—with the peak during winter, when the night tides are at their lowest. According to local custom, the best time for izari is marked by the arrival of migrating raptors from Siberia, and lasts from November to February.

Tools of the Trade

The standard equipment consists of a windbreaker, warm clothes, a powerful flashlight, a long-handled spear, and thick-soled boots to walk on the uneven coral and rock. People devise their own tools based on their experience and skills, but one standard is a traditional bamboo basket (ibiraku or teiru) that can be carried like a backpack to hold the day’s catch.

The Catch

The rocks and tide pools are rich with the ocean’s bounty. Many of the reef’s inhabitants are conveniently nocturnal, while others are asleep and slow to react, making them easier to catch. Turban shells, sea urchins, and crabs are plucked from crevices. Fish that are unable to escape to the sea are caught with spears. A wide range of people take part in this traditional method of fishing, from farmers taking a break from their sugarcane harvesting to families looking to stock their refrigerators or share their catch with friends and neighbors. The sight of their lights bobbing in the darkness off the coast is a memorable Amami Oshima scene.

Local Produce Shops

Supermarkets, convenience stores, and other shops can be found in the larger communities around the island. People in more distant communities, however, must rely on local produce shops that sell products directly from local farmers, fishermen, and other producers. Visitors are also welcome at these shops, where some of the best deals on island specialties and souvenirs can be found. Among the products available are fresh and processed fruit products, vegetables and other agricultural items, meat, fish, and local crafts. The variety ranges from papayas and passion fruit to brightly colored tropical fish, the traditional fermented drink called miki, and local brands of shochu. Many of the shops have rest areas and a corner where drinks and snack items are available, as well as bulletin boards featuring notices of upcoming events. The local residents running the shops are great sources of sightseeing tips. Even for those who are not interested in shopping, these small retailers can offer an insider’s look at the lives, traditions, and culture of the diverse island communities.